(f you are reading this, I apologize. It must be edited. This man named John gave me too much, and repeated himself.)

A man named John, an acquaintance, told me of his day on THIS day, Jaunary 7th, 2024. This happened on the west coast of Florida. It’s life:

Crows gather. They gather over the Culver’s burger place, a wavering black cloud. They are migrating from the cold and snow of the north. John’s long-time companion (they’ve never married)named Rosemary, loves crows. She is like a child in her love for crows. John love that she loves crows.

Seeing crows might make her happen for today. She has not been happy, and John knows he can’t make her happy. He can, however, make her unhappy, usually without meaning to.

He’s come from a rare visit to a church – he chose one, randomly, went, period. And resolved to live by the things he heard there– but instantly, as always, almost unavoidably he is in conflict with Rosemary. That’s life — January life where there is sunlight and no snow, but plenty of life.

He thinks: how did this happen? That I have made Rosemary unhappy?

Well, Rosemary is not feeling well. But he has never made her feel well, on top of her not feeling well physically. She says he does, but he knows he doesn’t.

For some reason, comforting John at this poiint, is an imaginary view across tidal flats to a little fishing village. It’s only a vision, a dream. There is no such village. This is a northern village. But, being imaginary, it is nowhere, but some imaginary cold place, probably New England from which John, like the crows, has migrated more than once.

For some reason, also comforting him, is a recurring thought of the time he traveled through Puerto Rico, alone. Or Europe, alone. He knows he may never get back. He’s in Florida. This is Florida life where people come with visions.

In his Puerto Rico dream, a woman is smiling at him, no woman he has ever known. If she knew him, she wouldn’t be smiling, or so he believes. Some women smile at everyone. The waitress at I-Hop called him, ”love.” She calls everybody “love.”

In the imagined European travel encounter, there is a smiling woman as well. She stands among the pigeons and the rain soaked stones of the Piazza San Marco. She might be the I-Hope waitress, a lovely African-American woman. She calls him “love” — just him.

But that’s good. Love is good.

But it is January 7th. Three times on this date, John, at three different workplaces, had bosses call him in. Yes, believe it or not — same date, three different years, three different jobs, three different odious summons from bosses. They had bad news for him –suddenly didn’t like his work. It never felt just. There were trumped-up circumstances. It was the beginning of the end of his time at those jobs where he’d been happy.

Rosemary wants to drive way out to a Florida strip center that has a bird shop in it, between the supermarket and the Chinese restaurant. She wants to get bird seed (that might attract those Crows over Culver’s) and eat at a little restaurant there, not the Chinese one.

John has things he wants to do. He wanted to write a book, but no one took him seriously on that. Small wonder. Besides, he feels he should want to do what Rosemary wants to do and make her happy, even if just for a while. He knows later in the day, after being miserable for a few h ours, she will be talking happily on the ph one to someone, or giving a way furniture. He thinks he’s agreeing when he nods, “yes”, though he’s unhappy inside. But Rosemary says, “why are you giving me that look?” They’ve been through this before, the ‘look.’

Standing before her, he goes off to that little New England seaside village in his mind, There is a light snow falling on the lobster pots and the roofs of the boat houses. There is no one around He approaches a pile of lobster pots. He sits on one after brushing off the snow. He is alone, looking across the inlet at a lighthouse.

His imagined fishing village and the memory of Puerto Rico and Europe and the smiling women do not coalesce with the highway and shopping malls and traffic he would have to endure to make the thirty-mile trip to the bird store and realize Rosemary’s dream. “That’s my ’Happy Place,'” she says to him, angrily, when it is too late for him to take back the ‘look’ he didn’t know he was giving her. He suggests they get bird seed at the chain hardware store. The birds have eaten itbefore. They’ll come and eat it again —maybe even the crows.

He doesn’t know what will bring the crows — maybe peanuts. He’s already put some peanuts out.

Rosemary has a $5 off coupon for the hardware store. That helps soften things.

Rosemary has things she wants to do. She says the woman across the street is selling a queen-sized bed.Rosemary wants a queen-sized for herself. She knows John likes to sleep at the far end of their king-sized bed. She’s resigned to that, apparently. He doesn’t want her to think that, but doesn’t want to make any changes. He wants to sleep alone, ultimately, in guest room bed. He wants to be alone allo the time. But he thinks changes like that can wait until January 8, which is what he thought last January 8th.

This is how he knows this:

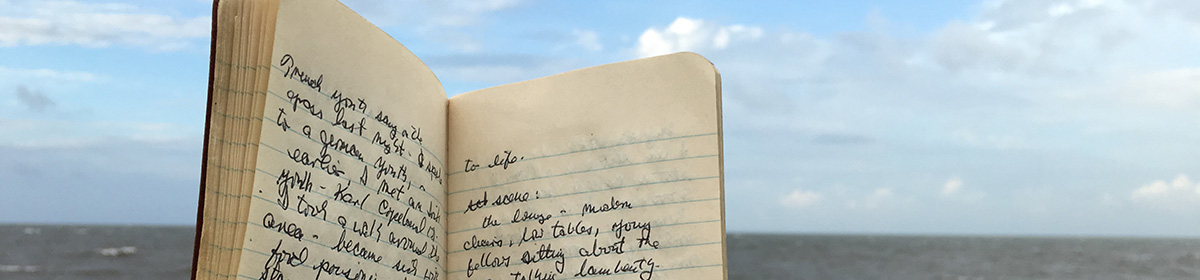

Last year on January 6th at 10:33 a.m., he wrote in his journal, “Trash out. What willl this year bring?”

Now he wonders, whatDID last year bring? He decides not to ask that question of himself anymore, that January New Year question. He’s tired of asking it. What’s the point?

It is Sunday. At the church he chose, they told him to pray. So, he’ll pray.

Last January on January 6 ( he made no entry for January 8th), he wrote, “Must take down the creche.” He and Rosemary are religious enough — or “spiritual” enough — to have put up a creche for Christmas. It’s tradition, after all. So, he could write again this year in his journal, if he were so inclined, ‘must take down creche.’ The child, Joseph, Mary, the shepherds, the newly arrived Magi from the East….

It was after he wrote “must take down the creche’ last year that he wrote, “what will this year bring?” Meaning the year just gone.

He admits to himself that he hoped he wouldn’t still be making Rosemary unhappy when he wrote that, a whole year ago. He wonders what he wrote the year before last year in January. They’ve been together more years than he cares to say. Or what did he write all those Januaries, all the way back to the turn of the century, and even before that. Early January is a rough time. The new beginning where nothing begins.

He reads poetry once in a while. He thinks of the poet who wrote….

Time present and time past

Are both present in time future…

And

In my beginning is my end…

And

I don’t know much about gods…

And

Midwinter spring is its own season

Sempiternal though sodden towards sundown,

Suspended in time, between pole and tropic.

Midwinter spring: he loves the thought of that, a sodden early spring, somewhere.

But, more than that — he thinks of a season “suspended in time.” He knows it is snowing in the north today. But sometimes spring comes for a while in midwinter. And sometimes, there are those times when time seems — suspended. Tiime present, time past, time future. He stands, suspended, in that little fishing village, in the Piazza San Marco, in Puerto Rico, and at the drive-up window at Culver’s burger place, and in the bird shop, with all its stacks of seed and bird houses and artificial bird sounds and smiling, friendly, bird-loving saleswomen who can tell you just what birds eat in what season.

What would they eat in a sempiternal, sodden season between seasons, suspended in time? Are not migrating birds suspended in time? Are there crows over the fishing village? Are there crows among the pigeons on the Piazza San Marco? Surely, they are in Puerto Rico. But no, he has read that the Puerto Rican crow, Corvus pumilis, is exinct. How sad. Gone from time. Haven’t any American crows thought of flying over there to get warm. It’s not that far.

He looks overhead and is glad to see the crows, seeming suspended in time, but real, so real. He hears their caws. Rosemary loves to hear the caws.

But he is happier in that fishing village, alone. There are no fishermen, no one, just the gulls. The crows — no they are imaginary, those crows over thar village, like the village itself, for the real crows are over his head, in Florida.

But at a time like this, he’d like to see that little fishing village, walk among the little buildings, idle for winter, gulls overhead, perhaps some crows. He would walk, in peace, alone. The village would be on a little inlet, leading out to the harbor, and then to the open sea.

He knows another one of Rosemary’s “Happy Places” is a lake in the north where she has spent some of her childhood. He has seen the home movies of her there, in the water, among cousins and aunts and uncles, and alone, the sun flashing between the trees. When they have been near that lake, he has taken her there. She found the old cottage on the little rise among the trees among other cottages on the lake. She left a little note and her address for the current owners who were absent (this was in winter). She told those strangers how much that little cottage had meant to her. She hoped to hear from them.

She heard nothing. No one ever wrote to her. John was sad for her.

They may not get that queen bed today. Maybe John will watch football. Rosemary is already watching a movie in the other room. She watches a lot of movies

She was experiencing hypoglycemia on top of her aggrivation and despair and unhappiness, so they had gone quickly to that Culver’s window and both ordered single burgers, his with pickles, lettuce, tomato and ketchup, her the same, only with onions. They both repeatedly told the girl talking to them on the speaker in the drive-thru that they didn’t want cheese on either of the burgers.

Just the same, her burger came with cheese.

He can hear her movie in the other room. He will sleep at the edge of that king-sized bed tonight. Changes can wait until tomorrow, and tomorrow. Maybe until next January 7th, 2025. At least he’s not working and so can’t get any bad news from employers today.

He has put sunflower chips bought with the $5-off coupon at Ace Hardware in the birdfeeders. Soon, he will look out and hope to see crows. He can call Rosemary to the window from her movie, make her happy on this January 7th.

They will eat leftovers for dinner. Some chicken, some pork, some thawed out frozen peas.

And tomorrow. Tomorrow he will go to the dentist.

They will be happy today. It is Sunday, January 7th.

They wonder what this year will bring.

They will look and listen for crows.