When I was working as an editorial assistant and occasional free-lance reporter for the Boston Globe back in the early 1970s, a reporter named Ann-Mary Currier, who occupied a desk near mine, wrote a splendid feature story about the little house that then stood along the shoreline on the far reaches of Cape Cod. It was called, Fo’castle, as on a ship. It would later come to be known as The Outermost House and evolve into a naturalist shrine surviving by the open ocean.

The book’s story, more than anything, was about Henry Beston, the 1st World War Navy veteran and nature-lover who moved into the tiny house for an entire year, that year being 1926-27. I don’t believe he built the house, which stood within the town of Eastham.

As I write about the house and Beston, I realize I may have written here about it and him before. No matter, I believe him — and the house — worthy subjects, and regard that year in which Beston lived alone with nature to be especially worth our time.

But when Ann-Mary’s story appeared in the Globe, it was the first I’d heard of either. I’m going to say the year was 1972. She interviewed, as I recall, surviving friends and relatives of Beston, who thought of himself as a writer-naturalist. I also recall a picture of Ann-Mary walking the wild, open stretch of beach with her interview subjects. Those photos appeared along with the story.

Nonetheless, it would be decades before I somehow came to do a televison story about the book, Outermost House, Beston and the society — The Henry Beston Society — that grew up around his book and his legacy.

Beston was a gifted writer who would turn out other books about New England seasons, but nothing remains as famous as Outermost House, published in 1928. A French edition of the book is called, Une Maison au bout du Monde (A House at the End of the World)

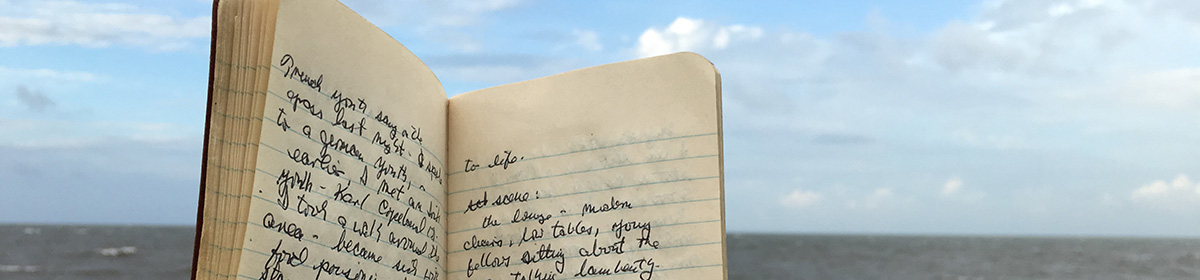

Beston spent that year in virtual seclusion making copious notes about everything he observed of the sea and the wildlife and the raw, active nature and impact of the tides encircling and buffeting his outermost locale. It is also a story of a fruitful solitude in what was essentially a two-room white cabin.

What prompted me to write about all this today was a desire, living in a Florida winter of only slightly dipping temperatures and grayer than usual skies in a community of vinyl, tin and wood modular homes, to write about a northern winter. They are having another fierce one up there.

But I also want to share with you a sample of Beston’s prose. Yes, I’ve probably done it before, but was it winter?

There is a chapter called, Midwinter. And Beston writes, after coming out of autumn, about the journey of the sun which he says is a far greater adventure than “(A) year indoors…(and)…”a journey along a paper calendar.

“…a year in outer nature is the accomplishment of a tremendous ritual. To share in it, one must have a knoweldge of the pilgrimages of the sun, and something of that natural sense of him and feeling for him which made even the most primitive people mark the summer limits.”

And so, Henry Beston has personified The Sun. The song writer wrote of Old Devil Moon. In fact, the moon gets lots of ink. I see both sun and moon as also having endearing female qualities — of warmth and nurturing….

But I’m wanderingly stupidly here, ruining things with my prattle. Back to Henry Beston….

“When all has been said,” he writes, “the adventure of the sun is the great natural drama by which we live, and not to have joy in it and awe of it, not to share in it, is to close a dull door on nature’s sustaining and poetic spirit.”

Beston is really no “sun worshiper.” He is — was — obviously just a naturalist- writer with the eye and soul of a poet. And poets see human qualities in everything, or so it has seemed since the time of the Romantics.

And, of the change from a Cape Cod autumn to a Cape winter, most likely in the autumn of 1926, Beston writes, “(T)he splendor of colour in this world of sea and dune ebbed from it like a tide; it shallowed first without seeming to lose ground and presently vanished all at once, almost, so it seemed, in one gray week. Warmth left the sea, and winter came down with storms of rushing wind and icy pelting rain. The first snow fell early in November, just before the dawn of a gray and bitter day.”

Then comes a visit to Outermost House by the postman. Henry certainly welcomed that visit as much as he welcomed the visit of the sun. He gave the postman a letter for mailing. Henry was alone, but, like me, he liked to stay in touch with people.

The postman departs, and he write…

“My fire had gone out, the Fo’castle was raw and cold, but my wood was ready, and I soon had a fire crackling.”

Beston died on April 15, 1968 at the age of 80. The Fo’castle — The Outermost House — was washed into the sea during the Blizzard of 1978. I believe a replica stands in hits place.

The memory of the original house survives, as does Henry Beston’s most original ruminations about his year on what writer Robert Finch (a Beston booster) has described as “that great glacial scarp of Cape Cod’s outer beach.”

Finch has written an eloquent introduction to later editions of the book. If y ou love nature and nature-writing, you’ll want to read his and Beston’s words on a region of my home state that, however drearily and insistently it gets overdeveloped, retains an enduring beauty.