(Part 3 of the 4-Part Barcelona quartet)

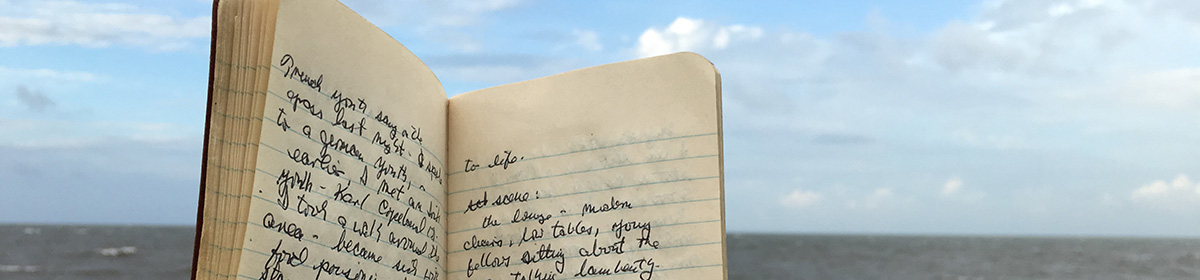

Mid-summer, 1966. Sparse, elliptical entries dot my flimsy 19-cent travel notebook from that period. Especially entries about my two-days in a broken down Barcelona youth hostel: Voices in the barren dusty hall below…. (sound of) a broom against the hard floor…children’s voices outside…it is cool and cloudy….I must write some letters and determine how I will get back to France….

Thereafter, unaided memory and only a few random, barely legible pen scratches help me reconstruct the moment in the wee hours when I woke to find a leg dangling by my bunk, then another, then both legs wiggling down to the floor below, using, if I recall accurately, my small suitcases for a stepping stone. Whoever’s legs these were had obviously missed curfew – probably a midnight curfew — and was climbing into the dormitory through a window. This particular window, right by my bed, had a broken screen, flapping loose, making possible this stealthy, illicit entrance. (Small wonder the dormitory was hungry with mosquitoes.) My initial annoyance was tempered by the memory of wandering lost in the city the night before. I could just as easily have missed curfew. A tolerant sense of fraternity seemed in order.

Presently one, perhaps two other youths slipped through the same window and quickly found their bunks. But the original arrivee, a lean and frenetic youth, circled briefly and restlessly in the dark, the hot red dot of a lighted cigarette arcing occasionally up to his mouth.

Someone smoking? In this fire trap? Again, tolerance, compounded by exhaustion, must have overridden outrage or alarm. I dozed off. Everyone else was snoring.

I met this smoker and curfew-breaker in the morning over the hostel’s meager bread and hot cocoa breakfast. He was a Danish boy about my age, his name forgotten. I don’t recall him smoking again, in or out of the hostel. Indoors, in sight of hostel proprietors, this would have violated strict rules – though this fellow seemed the kind of soul who was careless about rules: high-spirited, affable, dark blond, about nineteen. I don’t recall anything we spoke about, nor do I remember asking him the reason for his peculiar late night entrance. He was outgoing and lively in conversation, an ice-breaker among strangers. At some point, both of us must have befriended a young Scottish hostel guest. My notebook says: The Dane and Scot rode with me to the Placa Cataluña. I’d doubtless heard of the Placa’s splendor and decided to invite a hostel guest – the Scott – to travel there with me for lunch. By now, the Dane had gone off somewhere.

Sadly, I have no memory of this Scot. It’s obvious he struck me as a congenial travel companion. But once again, the Danish boy made himself memorable by rushing toward us as we headed for the door. Where were we going? He was eager and curious to know. Could he go, too? I realized then that, for all his sociability, this Danish kid was a solitary, perhaps lonely, traveler. He urged us to “wait a minute, will you?” speaking that axiomatic English phrase clearly and deliberately, making it unintentionally sound like a demand.

We must have traveled by taxi. I’m sure we had lunch. Sadly, I have no memory, written or otherwise, of the Placa Cataluña’s grand, storied ambiance and architecture or of my conversation with these newfound friends. Tweaking my subconscious, however, I believe I can see us in flashes – three strangers at an outdoor café table, the Danish boy doing much of the talking. Or did he become more reticent as the hours wore on?

Later, packed up, briefly idle, ready to depart the hostel for a final walk around central Barcelona before catching a night train to France, I was again approached by the Dane. He asked if I’d join him for a (quick) game of chess, if such a thing were possible. I agreed out of courtesy. We pulled chairs up to a ping-pong table and he removed a square plastic novelty from his belt where it had hung by a little chain. It was essentially a puzzles — a chess puzzle — with sliding black and white pieces designated as kings, queens, bishops, rooks, knights and pawns. He put this minute chessboard between us at one corner of the table. Then, speaking of puzzles, there followed a puzzling deliberative silence of a mere second or two. Without looking at me, the Dane suddenly asked, “do you like boys or girls?”

A very peculiar question at a time such as this. “Girls,” I answered quickly and with considerable emphasis, still puzzled, but suspicious — whereupon the Dane, giving a little chortle, abruptly flipped the tiny chessboard so that the tiny white squares faced me and the black squares faced him. He muttered something to the effect that his inquiry was merely a means of determining who’d play with which colored chess pieces.

Really? Why not just say, ‘do you prefer black or white?’

Was this just another among the multitude of trans-lingual misunderstandings or trans-cultural vagaries I’d occasionally encountered during my European travels? Musing over this antic moment after many years, I can’t say for certain, naïve as that sounds.

But, no matter. Only one or two rooks or pawns had slid about the miniature plastic board before we both, with a glance at our watches, declared it time to move on – I to the heart of Barcelona for a final look; him to wherever wild Danes went in that wide open decade.

His was among my briefest human encounters of that summer, although also among the more memorable. I now and then think of him – even say a little prayer for him — whenever I see a window with a broken screen.