There are all kinds of yells and shouts. Happy and sad ones, useful and necessary ones, warning ones.

It didn’t bother me in any way when I heard the guys out back of me briefly this morning find the need to yell. (In fact, I could barely hear this particular yell, or shout; I was just listening in fascination.) It was just one guy, in the course of his work; he was counting — counting, as in– one, two,three….

I’m surmising that he and his co-workers must have been lifting something, or lowering something. The one guy probably needed to yell so the other guys and he would be doing in concert whatever possibly risky task they were executing.

I had let the dog out and was filing the bird feeders. The men were at work beyond the parallell border of white PVC and chain link fencing and masking profusion of Brazilian pepper bushes.

I’ll bet those are hard working guys over there, though I don’t really know what they do. Move big things around., no doubt, laboring on this Thursday morning in some kind of warehouse whose function I’ve not yet — in six-going-on-seven years living here, bothered to ascertain. They ride around in bleating, rattling fork-lifts. It’s one of a million American workplaces where they perform some obscure but necessary function for the rest of us. God bless them.

Three times I heard yelled, “one….two…three….” Three times, something happened.

At the Space Center, when they work to lift off a rocket, they count in reverse….three, two, one….Lift Off!! Maybe they were lowering a rocket out back. Lift… Down!!

Just kidding.

I interviewed the retired editor of the Boston Globe and he recalled how, way back in the old days, a guy in the mailroom of the old Newspaper Row offices and presses announced the first press run of the morning edition by yelling, THEY’RE UP, THEY’RE UP, THEY’RE UP. (I don’t know if anybody was counting the papers as they rolled off. But everybody knew they were coming.

Jack Driscoll (the retired editor) sat in his wheelchair and repeated that memorable shout in the living room of his seaside New Hampshire home. It was almost as if he could hear the presses rumbling again.

I thought of that moment when I read of his death.

One of my earliest memories is a fleeting recollection of being on the streets of Boston’s North End with my parents and we were about to attend my late brother Bill’s graduation ceremonies from Christopher Columbus High School.

There was an Italian guy standing by a pushcart laden with fruit and vegetables and he was shouting.

I didn’t know what to make of it. Why was he shouting, and to whom? Of course, in time I’d know he was selling his produce, shouting for customers. Fresh tomatoes here!!!

My brother Doug worked after high school for the S.D. Warren Paper Company nestled in the heart of the city, very close to Boston’s primarily (in those days) Italian North End. He would come home and say how, every day, he heard some truck driver in the alley below –hear his echoing shout, Hey Wal-YO!”

I would learn from a history professor years later that this means, Hey, boy in Italian. It is apparently a common shouted Italian street greeting. In this case, it was probably coming from some Italo-American driver who made daily deliveries and needed someone to open a loading dock door –someone who knew their Italian. Just a guess.

Or maybe just one Italian fellow was greeting another as their round of daily work began. Shouting that greeting.

I recall being taken to my first-ever professional baseball game by my father. It was a Boston Braves game and there was a guy selling programs and, being very small and impressionable, still ignorant in the ways of theadult world (I was about six years old), I thought the guy was yelling up to the huge painted image of a feathered Indian brave on the stadium wall behind him — as if he expected the brave to answer him.

On November 9, 1957, I was barely eleven and was brought back to the same stadium, which, after the departure of the Braves for, first, Milwaukee, then Atlanta) became Boston University’s football home field . Today it is called Nickerson Field and retains some vestages of the old National League baseball venue, including the right field bleechers.

Of course, the image of the brave is long gone. But it was still on the stadium wall that November day in 1957, greatly faded. He had, in this frozen image, a feather still dangling from his hair and his mouth cupped with his hand — because he is supposed to be shouting, presumably an Indian war chant — just as he had been those four or five years before. Small wonder, in my six-year-old small and wondering mind, the program vendor and the massive Indian brave above and behind him appeared to be shouting to one another. (What could they possibly be saying to one another?)

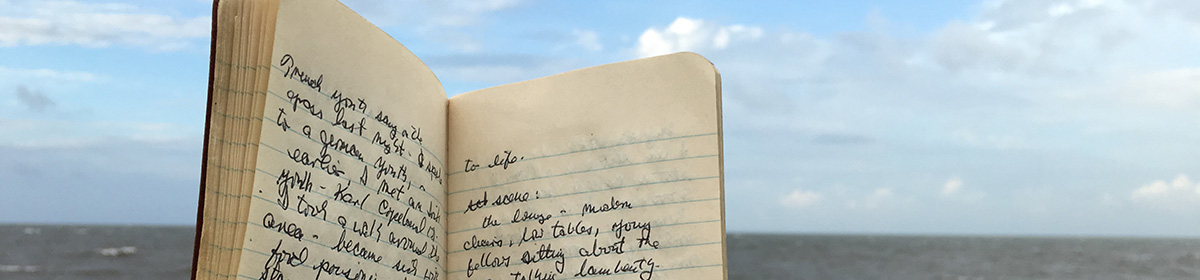

I recall a letter written by an American soldier from Vietnam, provided me for a story I was preparinig about the soldier and his wartime experiences. He wrote of being wakened from sleep in his tented, temporary billet by someone urgently yelling, MORTAR! MARTAR! and told his father — the recipient of the letter — how he clambored into a fox hole in his underwear, undoubtedly with other soliders, and had to be pulled from the depths of the probably muddy hole when the attack was over. It was not, alas, the final attack he would witness or, ultimately, survive.

I musn’t end that way — in war, in sorrow. I must believe that somewhere now on the planet — probably in many places — someone is shouting for joy.

Beginning in 1961, The Top Notes, the The Isley Brothers, then The Beatles exhorted us, happily, to twist and shout.

And in this primordially, perpetually twisted universe in which we are afflicted by Adam’s fall, we, in great hope — in Matthew 10:27 –are urged to shout from the rooftops the Good News.

So I guess there is good news. I’ll need a ladder to get to the rooftop.

And I hear those fellows over the fence, in shadow and sunlight. They — and I — are counting on it. The Good News, that is.

Maybe they’ve got a ladder I can borrow.