“I found this the other day,” said Joe Dunn.

Have I mentioned him before? He stops in the Mile once in a while. The Last Mile Lounge. When I saw him at a table, I went over and sat with him since I hadn’t seen him in a while. I think he used to live in the neighborhood, lives in New Hampshire now and stops by the Lounge when he’s in town to say hello to Deano at the bar and anybody else he recognizes. I think he’s retired. I’ve seen him get real gray all of a sudden.

He was holding a little envelope. He’d pulled the card out of it. It had a nice picture, a painting on the front, colorful, cartoonish, very whimsical — of ramshackled little cabins, two of them side by side, presumably on some tropical island with a palm tree and boat up on blocks behind it, a pudgy cat sleeping on the porch of one, old screen door swung open on the other,a couple of plants on the railing of one, one next to the steps of both cabins, broken down white picket fence between the two. It’s the sort of happy slovenliness that denotes ultimate away-from-it-all oceanside leisure, typically of a Gulf-side Florida fisherman’s village. It was just a painting, of course; an endearing bit art on a greeting card. But looking at it took me someplace I’d like to have been at that moment, away from cool, gray Boston. I guess it took Dunn there, too.

“I found it with some letters, old letters I didn’t know I’d tucked away,” Dunn said. “It’s from when I was working in Florida, going back to the early Eighties. A long time ago. I was doing a shift at a little radio station on a little Gulf coast island.”

I’d forgotten Dunn had been on the radio; been kind of a start-up disc jockey at the smallest possible wattage station. Sounded like fun. But he didn’t stay there long. He was trying to build his broadcast career. He took a job in St. Petersburg.

“I’d spent some time with these people,” he said. “This couple, they were some of the people I’d get together with, party with, sail around with when I was down there living on the island. I’d been to their place a few times for parties. There were some beautiful island nights. We weren’t real close friends, I wasn’t there long enough to make close friends. They had a boat. A sailboat.

“Take a look at what she wrote,” he said. “I mean what Estrella had to say. Her name was Estrella. She was pretty, about my age. I think she was –oh, Hispanic, I guess. Maybe second-generation Mexican or Puerto Rican. Whatever. Last name was Querrero. Her boyfriend was a nice guy. I don’t think they were married. His name was Keith.

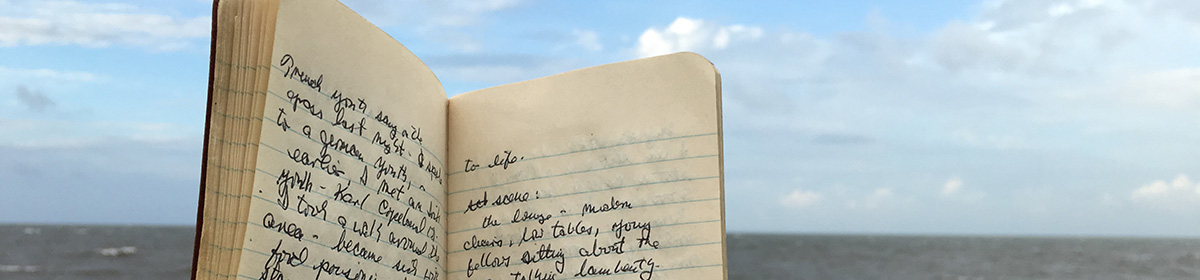

“Like I say, I didn’t really feel like I knew them that well. I was just another guy. Just another guy going to parties. We were all kind of young. And this note, it came from Estrella, not him. Look at that neat handwriting. She took the time to write this to me on this neat little card.”

Ole Joe Dunn was getting carried away.

I set down my bitters and soda, a little concoction I like to drink once in a while since I don’t drink. (I come to The Mile for company, and memories. Dunn came with his memories, that’s for sure — and on this night, his memories were w ritten on that little card he’d found — and saved. ( I save some letters, too, but all the way back to 1981?) But here was Joe with his letter at the Last Mile — he brought with him to have a beer over, remember old, probably better, maybe more innocent times. Maybe was — now that he thought about it — might have been the start of a romance that he missed! (We can all be foolish this way once in a while.)

“I remember thinking when I got it how surprised I was Estrella was writing me,” Dun said. ” No mention of Keith. It’s when I realized I’d left the island without saying goodbye. And I didn’t think Estrella ever really noticed me that much when I was around. We talked. Hell, I talked to everybody. I guess maybe we talked more than I realized. We didn’t flirt, just talked. Maybe I talked to her more than Keith. Maybe she was lonely. He worked at the local planning office. Probably worked long hours. He was big on protecting the environment. Like I say, nice guy.”

I held the card and read it. It was dated 2/2/81. It said,

Well, darn! What are you doing in St. Petersburg?! I’m glad you received our xmas card and let us know where you are. Wish we could have seen more of you, though. If you’ve ever got a few days off, or just happen to be in the area, please come see us, OK?

There was more — about days sailing on the Gulf and around Pine Island Sound, about the bad winter of so far that year, the rain that was falling that day she was writing that letter. This Estrella packed a lot into that little card — and, yes, in very nice, neat handwriting.

She ended the little note saying, Everyone here is doing fine and sends their regards and best wishes. Keep in touch.

Dunn looked at me. “Never once did she mention Keith.”

“No, she never did,” I said, still holding the card, which I looked down at again. At the very end of the note, almost off the edge of the card at the bottom (very neatly, almost, it seemed, with even a little more care, like a person pausing in conversation so their next few words will get your attention), she wrote, “love you.” Not just, “love.” But love you. The ink even seemed a little darker, as if she were moving the pen more slowly, perhaps trying not to wind up going off the card altogether, but also not wanting the reader to miss it. Joe Dunn was the reader. He looked at me and said, “what do you think?”

“I don’t really think anything, but I guess you think she was sweet on you,” I said, which is what I figured he wanted me to say — and, truthfully, I didn’t know, one way or the other. I handed the card back to him. He looked at it for a long time, then slip it back into the envelope bearing a 15 cent stamp. (It was 1981; postage was cheaper). “She may still be wondering where you are,” I said, though I truly believed she’d probably forgotten all about him. “Did she ever marry that boyfriend?”

Dunn looked a little stricken. He said, “they broke up right about that time. I heard that through the grape vine.” He put the envelope down on the table next to his Budweiser. Three or four people came in the bar at that point. I’d never seen any of them before, but they looked local and were kind of noisy. Some shift at some restaurant must have ended and these were the employees coming in for a night cap.

“So maybe Estrella was trying to tell me something,” Dunn said over the noise. “Maybe that she was going to be –free. Maaybe she was breaking up with Keith.”

“I don’t gdt that in that note,” I said, truthfully.

“They got my Christmas card,” he said addressed to both of them, in response to their Christmas card. She did say ‘we’ in that note. Not ‘I.” They seemed happy together. I was surprised to hear about the breakup.

“But look at the date on the letter — 2/2/81. That was the very day my first wife came back looking to start things up again and wound up taking all the oxygen out of my life, kind of took me hostage.”

“That’s a little strong,” I said.

“Maybe so,” he said. “But the fact is, I got this letter when my options had suddenly shrunk — or disappeared. I must have been preoccupied with my new situation, because I don’t remember seeing that, ‘love you” or giving any thought to responding one way or another.”

I felt it was my obligation then to say,”don’t read too much into that note, Joe. Women write that kind of stuff a lot to friends, male and female. They don’t mean anything by it. She probably –they both probably just liked you as a person, as a friend. You are a fun guy, after all. Very charming.” I patted him on the back. “That’s what the women tell me, anyway.” I laughed and he laughed. He sipped his beer. I sipped my bitters.

“And you hardly knew her,” I added. “She was about to break up. So what? Maybe you’d have gotten together, found out you didn’t have anything in common.”

Dunn was thinking about all that. “She was really attractive, really nice, really smart,” he said. I must not have picked up on what she was thinking or feeling about me.”

“She might have been feeling nothing,” I said. “You’re just reading into it.”

“You just said maybe she was sweet on me,” he said.

“Yeah, I did, didn’t I? Well, the truth is, how do I know? I’m just saying…”

Then iin dawned on me and i I pointed out to him that there was a phone number in that note on that card. I think I saw a light bulb light up over his head. He quickly took the car out aof its envelope gain. “Sure enough,” he said. “She included a phone number.”

I reminded him that there were no cell phones in ’81. . So it must have been ‘their’ number. A house phone. Were they living together?”

“Yes.”

“So it was their phone. A landline house phone.” Then I sat back and got a bold idea.

“Joe, did you ever call that number?”

He had to think for a minute, then said, “no. And I never went back down to the island again– or not that year or any time until the nineties. Well after ’81.

“Call it,” I said. “Call the number — just for the hell of it.”

“That’d be crazy,” Dunn said. “This was forty-three years ago. She’s probably married to somebody, got kids, the whole works. Probably moved away — miles away.” But he was plainly thinking about it.

“I wish I’d picked up on — whatever,” he said. ” I’m starting to remember being swiming with her kinid of alone, and another time when she was was pulling herself back up into the sailboat and I was behind her, climbing in after her — she had on this nice bathing suit, she really had a nice figure. She had dark hair, she was wearing nice sunglasses as we sailed around. She and Keith took turns handling the sailing duties…I decided right then I’d take up sailing….” He just sat there, remembering. He looked down at the number. “I never did,” he said. “And I never called this number.”

“Call it, ” I said. “Sometimes people stay in the same place, keep the same numbrer forever. Was it her place or his?”

“I don’t know.”

“Well, if he answers, just say, ‘hey, remember me? Just found this number and was wondering how you’re doing? ‘ If she answers –well, it’ll be one of those, ‘I don’t know if you remember me but, funny thing, I just found this card…'”

“Greg,” he said, staring at me. ” Neither of them would remember me. It would be awkward as hell, really stupid.”

“But, I said, “you’d like to think she remember you, right? It sounds like you made an impression on them — especially on her.”

He sat back in his chair, flipping the little card side to side on the table. “Right,” he said.

“You’d like to think Keith would pick up and say,’Hi, Joe, great to hear your voice. Say Estrella really liked y ou and she’s living in Boston now. And she’s single and she’d really like to hear from you. She really liked you.’ That’s what you’d like to hear, right?

Joe looked at me, smirked, shook his head. “This is all ridiculous. Any call like that would be awkward as hell…”

“Right, but it’s bothering you, so you could say you were interested in that island and wanted to talk to the only people you recalled — and hope she recalls…

Joe said, “I knew them for, what? a summer and a fall? On a Florida island, where nothing ever seemed part of the real world….hot breezy summer days, tourists all around, sparkling Gulf of Mexico waters. Unreal. Truth is, until I found this card, I’d probably forgotten about both of them.”

At that point, I tried to talk about something else — it was definitely time for that — like the fact the Bruins were out of the running for the Stanley Cup. But Dunn, even being a big Bruins fan, was transfixed, staying somewhere back in his past –with Estrella. I could tell.

I knew from talking to him in the past that his ex-wife went out of his life just about as quickly as she came back into it back in ’81. I knew he started drinking kind of heavily and had a bunch of relationships, got married again, divorced again. But tonight, all he could think about was Estrella.

I decided it was time for me to go. I shook JOe’s hand. He smiled. “Thanks for listening,” he said. I stood up and said, tapping the little letter with my finger. “Call that number. I know you want to do it. You’ve got nothing to lose.”

Greg,” he said, giving me a sharp knife’s glare, “I know you don’t mean that. You’re a sensible guy. It was a long time ago. I’m dreaming, living in that island past. We’re old, you and me. You can call up the past in your mind — but you can’t call it up on the telephone.”

What could I say? He was right. I’d been wrong to even encourage him to dream about something that was long gone and might never have been there in the first place.

But, for the hell of it, I said, “Maybe you can –pull up the past on a telephone, that is.” I was pulling on a light jacket as I said it. It was a little chilly out. “Maybe this is the Twilight Zone,” I said. “Maybe you’ve got a mysterious phone that can call up the past.”

He chuckled, then waved goodbye, tucking the card back in the envelope and stuffing it in the breast pocket of his shirt. I took my empty glass up and set it on the bar in front of Deano, who thanked me. It was Sunday night but quite a few people were sitting along the bar, bracing for Monday, including those three late arrivals.

As I walked to the door, I looked back at Dunn. He had the card back out on the table, was reading from it. He had his cell phone out, and looked like he punching in the number off the card. At this hour? It was about nine at night. You don’t even call people you know that late. Could it be? Could he — or maybe his Budweiser — be making that call? He didn’t have a wife anymore (that’s another whole story.) I’d made the mistake of suggesting he had nothing to lose (thought he might quickly lose his illusions. The number was so old, he might get some old man or old lady on the island, even wake them from a sound sleep….

Lonely people drinking beer can do stupid things.

But then, I saw him pause, stuff both the card and his phone in his pocket and just sit back, a look of profound resignation traveling all around his Irish-American face under his thinning gray-haired head.

Joe Dunn ultimately was a man for whom the Iceman had Cometh, as it were, as it comes for all of us sooner or later. He knew that what romance might have been– for what little it was worth or as briefly as it might have lasted — was irretrievable. Estrellas ,a lovely name for an undoubtably lovely, once-young woman of Joe’s acquaintance, was back there in 1981, living on an island of lost time, unreachable other than by the small, frail boat of memory.

And I knew he’d never call that number.